Ain't is a contraction for

am not,

is not,

are not,

has not, and

have not in the common English language

vernacular. In some dialects

ain't is also used as a contraction of

do not,

does not, and

did not. The development of

ain't for the various forms of

to be not,

to have not, and

to do not occurred independently, at different times. The usage of

ain't for the forms of

to be not was established by the mid-18th century, and for the forms of

to have not by the early 19th century.

The usage of

ain't is a perennial subject of controversy in

English.

Ain't is commonly used by many speakers in oral or informal settings, especially in certain regions and dialects. Its usage is often highly stigmatized, and it may be used as a marker of socio-economic or regional status or education level. Its use is generally considered non-standard by dictionaries and style guides except when used for rhetorical effect, and it is rarely found in formal written works.

Etymology[edit]

Ain't has several antecedents in English, corresponding to the various forms of

to be not and

to have not that

ain't contracts. The development of

ain't for

to be not and

to have not is a

diachronic coincidence;

[1] in other words, they were independent developments at different times.

Contractions of to be not[edit]

Amn't as a contraction of

am not is known from 1618.

[2] As the "mn" combination of two nasal consonants is disfavoured by many English speakers, the "m" of amn't began to be

elided, reflected in writing with the new form

an't.

[3] Aren't as a contraction for

are not first appeared in 1675.

[4] In

non-rhotic dialects,

aren't lost its "

r" sound, and began to be pronounced as

an't.

[5]

An't (sometimes

a'n't) arose from

am not and

are not almost simultaneously.

An't first appears in print in the work of

English Restoration playwrights.

[6] In 1695

an't was used as a contraction of "am not", in

William Congreve's play

Love for Love: "I can hear you farther off, I an't deaf".

[7] But as early as 1696

Sir John Vanbrugh uses

an't to mean "are not" in

The Relapse: "Hark thee shoemaker! these shoes an't ugly, but they don't fit me".

[8]

An't for

is not may have developed independently from its use for

am not and

are not.

Isn't was sometimes written as

in't or

en't, which could have changed into

an't.

An't for

is not may also have filled a gap as an extension of the already-used conjugations for

to be not.

[6] Jonathan Swift used

an't to mean

is not in Letter 19 of his

Journal to Stella(1710–13):

It an't my fault, 'tis Patrick's fault; pray now don't blame Presto.[9]

An't with a

long "a" sound began to be written as

ain't, which first appears in writing in 1749.

[10] By the time

ain't appeared,

an't was already being used for

am not,

are not, and

is not.

[6] An't and

ain't coexisted as written forms well into the nineteenth century—

Charles Dickens used the terms interchangeably, as in Chapter 13, Book the Second of

Little Dorrit (1857): "'I guessed it was you, Mr Pancks," said she, 'for it's quite your regular night; ain't it? ... An't it gratifying, Mr Pancks, though; really?'". In the English lawyer

William Hickey's memoirs (1808–1810),

ain't appears as a contraction of

aren't; "thank God we're all alive, ain't we..."

[11]

Contractions of to have not[edit]

Han't or

ha'n't, an early contraction for

has not and

have not, developed from the elision of the "s" of

has not and the "v" of

have not.

[6] Han't appeared in the work of English Restoration playwrights,

[6] as in

The Country Wife (1675) by

William Wycherley:

Gentlemen and Ladies, han't you all heard the late sad report / of poor Mr. Horner.[12] Much like

an't,

han't was sometimes pronounced with a long "a", yielding

hain't. With

H-dropping, the "h" of

han't or

hain't gradually disappeared in most dialects, and became

ain't.

[6]

Ain't as a contraction for

has not/have not first appeared in dictionaries in the 1830s, and appeared in 1819 in

Niles' Weekly Register:

Strike! Why I ain't got nobody here to strike....[13] Charles Dickens likewise used

ain't to mean

haven't in Chapter 28 of

Martin Chuzzlewit (1844):

"You ain't got nothing to cry for, bless you! He's righter than a trivet!"[14]

Like with

an't,

han't and

ain't were found together late into the nineteenth century, as in Chapter 12 of Dickens'

Our Mutual Friend: "'Well, have you finished?' asked the strange man. 'No,' said Riderhood, 'I ain't'....'You sir! You han't said what you want of me.'"

[15]

Contractions of to do not[edit]

Ain't meaning

didn't is widely considered a feature unique to

African American Vernacular English,

[16] although it can be found in some dialects of

Caribbean English as well.

[17] It may function not as a true variant of

didn't, but as a creole-like tense-neutral negator (sometimes termed

generic ain't).

[16] Its origin may have been due to approximation when early African-Americans acquired English as a second language; it is also possible that early African-Americans inherited this variation from colonial European-Americans, and later kept the variation when it largely passed out of wider usage.

Ain't is rarely attested for the present-tense constructions

do not or

does not.

Linguistic characteristics[edit]

Linguistically,

ain't is formed by the same rule that English speakers use to form

aren't and other

contractions of auxiliary verbs.

[3] Most linguists consider usage of

ain't to be grammatical, as long as its users convey their intended meaning to their audience.

[18] In other words, a sentence such as "She ain't got no sense" is grammatical because it generally follows a native speaker's word order, and because a native speaker would recognize the meaning of that sentence.

[19] Linguists draw a distinction, however, between grammaticality and acceptability: what may be considered grammatical across all dialects may nevertheless be considered not acceptable in certain dialects or contexts.

[20] The usage of

ain't is socially unacceptable in some situations.

[21]

Functionally,

ain't has operated in part to plug what is known as the "

amn't gap" – the anomalous situation in standard English whereby there are standard contractions for other forms of

to be not (

aren't for

are not, and

isn't for

is not), but no standard contraction for

am not. Historically,

ain't has filled the gap where one might expect

amn't, even in contexts where other uses of

ain't were disfavored.

[22] Standard dialects that regard

ain't as non-standard often substitute

aren't for

am not in

tag questions (e.g., "I'm doing okay,

aren't I?"), while leaving the "amn't gap" open in

declarative statements.

[23]

Prescription and stigma[edit]

Ain't has been called "the most stigmatized word in the language,"

[24] as well as "the most powerful social marker" in English.

[25] It is a prominent example in English of a

shibboleth – a word used to determine inclusion in, or exclusion from, a group.

[24]

Historically, this was not the case. For most of its history,

ain't was acceptable across many social and regional contexts. Throughout the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries,

ain't and its predecessors were part of normal usage for both educated and uneducated English speakers, and was found in the correspondence and fiction of, among others,

Jonathan Swift,

Lord Byron,

Henry Fielding, and

George Eliot.

[26] For Victorian English novelists

William Makepeace Thackeray and

Anthony Trollope, the educated and upper classes in 19th century England could use

ain't freely, but in familiar speech only.

[27] Ain't continued to be used without restraint by many upper middle class speakers in southern England into the beginning of the 20th century.

[28][29]

Ain't was a prominent target of early

prescriptivist writers. In the 18th and early 19th centuries, some writers began to propound the need to establish a "pure" or "correct" form of English.

[30] Contractions in general were disapproved of, but

ain't and its variants were seen as particularly "vulgar."

[24] This push for "correctness" was driven mainly by the middle class, which led to an incongruous situation in which non-standard constructions continued to be used by both lower and upper classes, but not by the middle class.

[27][31]The reason for the strength of the prescription against

ain't is not entirely clear.

The strong prescription against

ain't in standard English has led to many misconceptions, often expressed jocularly (or ironically), as "ain't ain't a word" or "ain't ain't in the dictionary."

[32] Ain't is listed in most dictionaries, including the

Oxford Dictionary of English[33] and Merriam-Webster.

[34] However, Oxford states "it does not form part of standard English and should never be used in formal or written contexts,"

[33] and Merriam-Webster states it is "widely disapproved as non-standard and more common in the habitual speech of the less educated".

[34]

Webster's Third New International Dictionary, published in 1961, went against then-standard practice when it included the following usage note in its entry on

ain't: "though disapproved by many and more common in less educated speech, used orally in most parts of the U.S. by many cultivated speakers esp. in the phrase

ain't I."

[35] Many commentators disapproved of the dictionary's relatively permissive attitude toward the word, which was inspired, in part, by the belief of its editor,

Philip Gove, that "distinctions of usage were elitist and artificial."

[36]

Regional usage and dialects[edit]

From Mark Twain,

Life on the Mississippi, 1883

Ain't is found throughout the English-speaking world across regions and classes,

[37] and is among the most pervasive nonstandard terms in English.

[38] It is one of two negation features (the other being the

double negative) that are known to appear in all nonstandard English dialects.

[39] Ain't is used throughout the United Kingdom, with its geographical distribution increasing over time.

[40] It is also found throughout the United States, including in Appalachia, the South, New England, the Mid-Atlantic, and the Upper Midwest.

[25] In its geographical ubiquity,

ain't is to be contrasted with other folk usages such as

y'all, which is confined to the South region of the United States.

[41]

In England,

ain't is generally considered a non-standard or illiterate usage, as it is used by speakers of a lower socio-economic class, or by educated people in an informal manner.

[42] In the nineteenth century,

ain't was often used by writers to denote regional dialects such as

Cockney English.

[43] Ain't is a non-standard feature commonly found in mainstream Australian English,

[44] and in New Zealand,

ain't is a feature of Maori-influenced English.

[45] In American English, usage of

ain't corresponds to a middle level of education,

[42] although it is widely believed that its use establishes of lack of education or social standing in the speaker.

[46]

The usage of

ain't in the southern United States is distinctive, however, in the continued usage of the word by well-educated, cultivated speakers.

[47] Ain't is in common usage of educated Southerners.

[48] In the South, the use of

ain't can be used as a marker to separate cultured speakers from those who lack confidence in their social standing and thus avoid its use entirely.

[49]

An American propaganda poster from World War II, using

ain't for rhetorical effect

Rhetorical and popular usage[edit]

Ain't can be used in both speech and writing to catch attention and to give emphasis, as in "Ain't that a crying shame," or "If it ain't broke, don't fix it."

Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary gives an example from film critic

Richard Schickel: "the wackiness of movies, once so deliciously amusing, ain't funny anymore."

[50] It can also be used deliberately for what

The Oxford Dictionary of American Usage and Style describes as "

tongue-in-cheek" or "

reverse snobbery".

[51] Star baseball pitcher

Dizzy Dean, a member of the

Baseball Hall of Fameand later a popular announcer, once said, "A lot of people who don't say ain't, ain't eatin'."

[52]

Although

ain't is seldom found in formal writing, it is frequently used in more informal written settings, such as popular song lyrics. In genres such as traditional country music, blues, rock n' roll, and hip-hop, lyrics often include nonstandard features such as

ain't.

[53] This is principally due to the use of such features as markers of "covert identity and prestige."

[53]

Ain't is standard in some

fixed phrases, such as "You ain't seen nothing yet".

Notable[edit]

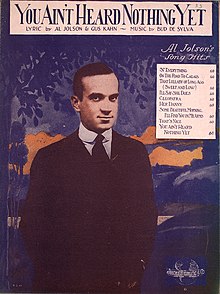

"You Ain't Heard Nothing Yet", 1919

- "Ain't I a Woman?", 1851 speech by abolitionist Sojourner Truth.[54]

- "If you want to know who we are", from The Mikado lyrics by W. S. Gilbert "We figure in lively paint: Our attitude's queer and quaint—You're wrong if you think it ain't." (1885).[55]

- George Bernard Shaw's play Pygmalion "I ain't done nothing wrong by speaking to the gentleman."[56]

- Great baseball hitter Wee Willie Keeler's advice to young hitters was: "Keep your eye clear, and hit 'em where they ain't."

- "Say it ain't so, Joe!", apocryphal quote from a young baseball fan to Shoeless Joe Jackson after the fan learned about the Black Sox scandal involving throwing the 1919 World Series.[57] "Say it ain't so" was subsequently used as the title of a song by Weezer and analbum by Murray Head, among other artistic works.

- "You ain't heard nothing yet!" spoken by Al Jolson in The Jazz Singer (1927), the first feature-length motion picture with synchronized dialogue sequences.[58]

- "It Ain't Necessarily So", song from Porgy and Bess (1935); music by George Gershwin, words by Ira Gershwin.[59]

- "He ain't heavy, he's my brother" has been used as the motto of Boys Town since 1943,[60] and inspired a song He Ain't Heavy, He's My Brother, written by Bobby Scott and Bob Russell, and recorded by The Hollies, Neil Diamond, and other artists.

- "Ain't That a Shame" is a song written by Fats Domino and Dave Bartholomew, released by Imperial Records in 1955, which went on to sell over a million copies and introduced Fats Domino to a wider audience.[61]

- "Ain't No Mountain High Enough" is a song written by Nickolas Ashford & Valerie Simpson, recorded by Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell for Motown Records in 1967, and again by Diana Ross for Motown in 1970.

- "You Ain't Seen Nothing Yet" is a song written by Randy Bachman and performed by Bachman–Turner Overdrive (BTO) on the album Not Fragile (1974).